SOME EXCERPTS FROM OUR NEWSLETTER

We produce two Newsletters a year all full of stories of Clan Fraser and its Septs. Below is a tiny selection of those interesting articles, why not join the Society, £10 for a UK member is fantastic value, at today’s prices, fill in a Joining form and send it off and you can be enjoying these articles on a regular basis.

HAUGHS O CROMDALE

When touring Scotland last year and staying at Grantown on Spey, we drove through the Haughs, which reminded me of an old Corrie song I still love, The Haughs o Cromdale, “where the Frasers fought wi sword and lance, the Grahams made the heids tae dance”, I felt as though it was almost personally written for me. Now this song does have a great tune yet I’d never studied the lyrics very closely, so perfect time for an investigation but much to my surprise, I found the lyrics are two events cobbled together by some unknown bard and the events had a gap of many years between them. Could this possibly have been for political reasons, as well as making a great song, let’s see?

When sung I’ve always heard them in Scots but any published version seem to be sanitised into some half English language version, so let your imagination take priority when going through the acts of great daring do below, NB “a daring do is a brave pigeon in Scots, it can be a difficult language”.

Haughs o’ Cromdale

As I came in by Auchindoun,

A little wee bit frae the toun,

When to the Highlands I was bound,

To view the haughs of Cromdale,

I met a man in tartan trews,

I speir’d at him what was the news;

Quo’ he the Highland army rues,

That e’er we came to Cromdale.

We were in bed, sir, every man,

When the Engligh host upon us came,

A bloody battle then began,

Upon the haughs of Cromdale.

The English horse they were so rude,

They bath’d their hooves in Highland blood,

But our brave clans, they boldly stood

Upon the haughs of Cromdale.

But, alas! We could no longer stay,

For o’er the hills we came away,

And sore we do lament the day,

That e’er we came to Cromdale.

Thus the great Montrose did say,

Can you direct the nearest way?

For I will o’er the hills this day,

And view the haughs of Cromdale.

Alas, my lord, you’re not so strong,

You scarcely have two thousand men,

And there’s twenty thousand on the plain,

Stand rank and file on Cromdale.

Thus the great Montrose did say,

I say, direct the nearest way,

For I will o’er the hills this day,

And see the haughs of Cromdale.

They were at dinner, every man,

When great Montrose upon them came,

A second battle then began,

Upon the haughs of Cromdale.

The Grant, Mackenzie and MacKay,

Soon as Montrose they did espy,

O then, they fought most valiantly!

Upon the haughs of Cromdale.

The Macdonalds they returned again,

The Camerons did their standard join,

MacIntosh play’d a bloody game,

Upon the haughs of Cromdale.

The MacGregors fought like lions bold,

MacPhersons, none could them control,

MacLaughlins fought, like loyal souls,

Upon the haughs of Cromdale.

MacLeans, MacDougals, and MacNeils,

So boldly as they took the field,

And make their enemies to yield,

Upon the haughs of Cromdale.

The Gordons boldly did advance,

The Frasers fought with sword and lance,

The Grahams they made the heads to dance,

Upon the haughs of Cromdale.

The loyal Stewarts with Montrose,

So boldly set upon their foes,

And brought them down with Highland blows,

Upon the haughs of Cromdale.

Of twenty thousand Cromwell’s men,

Five hundred fled to Aberdeen

The rest of them lie on the plain,

Upon the haughs of Cromdale.

The Battle of the Haughs of Cromdale took place on April 30 and May 1, 1690, where “the loyal Stewarts, wi’ Montrose, laid them low wi’ Hi’land blows and of twenty-thousand Cromwell’s men, a thousand fled to Aberdeen” Now a bit of a giveaway to this not being right is, Montrose died in 1650, Cromwell died in 1658 and this battle was part of the first Jacobite Rising in 1689 and was a total rout of the Jacobites. The Frasers did fight and were victorious, for the Rightful King, under James Graham of Claverhouse, Bonnie Dundee, at Killiekrankie in July 1689, where Claverhouse lost his life, we were at the consequent defeat at Dunkeld in August 1689 but by 1690 I’ve a feeling we just took our “sword and lance” and went home.

To get to the other battle, we unbelievably, have to go back 45 years to the Battle of Auldearn, Nairn, 1 May 1645, where the Frasers helped James Graham, Marquis of Montrose or the Great Montrose, to a victory over Cromwell’s men, or did we? Now, this wasn’t a Jacobite uprising, they hadn’t been invented yet but part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms as part of the First English Civil War, it was a great victory for the Great Montrose and his 2,000 men, accounts of numbers do vary but there weren’t “20,000 Cromwell’s men”, only up to 5,000, of which 1,200 were casualties and Aberdeen was a long flee at 85 miles, even nowadays it takes ages by bus. Yes, the Frasers did fight at this battle but no, the song is wrong again, we fought against Montrose “wi’ sword and lance” on the side of Cromwell and the Covenanters, led by Fraser of Struy, it’s said 87 Fraser widows were left, after the battle but whilst there’s some reports in a poem of Frasers fighting Fraser, if there were members of our clan with Montrose, I can’t find any organised force.

to the Battle of Auldearn, Nairn, 1 May 1645, where the Frasers helped James Graham, Marquis of Montrose or the Great Montrose, to a victory over Cromwell’s men, or did we? Now, this wasn’t a Jacobite uprising, they hadn’t been invented yet but part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms as part of the First English Civil War, it was a great victory for the Great Montrose and his 2,000 men, accounts of numbers do vary but there weren’t “20,000 Cromwell’s men”, only up to 5,000, of which 1,200 were casualties and Aberdeen was a long flee at 85 miles, even nowadays it takes ages by bus. Yes, the Frasers did fight at this battle but no, the song is wrong again, we fought against Montrose “wi’ sword and lance” on the side of Cromwell and the Covenanters, led by Fraser of Struy, it’s said 87 Fraser widows were left, after the battle but whilst there’s some reports in a poem of Frasers fighting Fraser, if there were members of our clan with Montrose, I can’t find any organised force.

Now, what to make of this confused but great song, was it a political jumble of words to help the Jacobite cause, an early form of “False News”, was it a mix up between the names of the two Montroses, did “lance and dance” make a good rhyme or “Is This Just Fantasy”, to quote Queen, the pop group that is, not the Hanoverian one? Well, no one knows, I’m still confused, historically, we fought first for the Covenanters against Montrose and Charles I, then for the other Montrose and James VII, against the Covenanters and got beat both times, although come Cromdale both Montroses were dead and we may have just been under our duvets at home but disnae yer taes drum fan the pipe band starts tae play one o the world’s greatest pipe tunes! Editor, Graeme, (the head dancer), Fraser, (with or without sword and lance).

EDINBURGH TATTOO

The Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo has unveiled the 2017 theme as “Splash of Tartan” taking inspiration from VisitScotland’s events for the year, Clan Chiefs have been invited to lead their clansmen to the Castle, on their own special designated evenings, and to take part in the opening ceremony of the Tattoo. In addition, clans and families are being encouraged – with some support from the Scottish Government through the Scottish Clan Event Fund: Splash of Tartan – to arrange their own events, as well. In each performance of the Tattoo in 2017, in collaboration with the Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs, identified clan chiefs will take the salute, in front of their clan members. As you well know there’s a lot of clans and a lot of chiefs, therefore, each one has been given a set date for their salute.

My mother, Lady Saltoun, has asked if I can organise our involvement as Clan Fraser at the Tattoo and I’m asking for as many of you as possible to join this wonderful event and play your part for Clan Fraser in Edinburgh. It’s not only a great honour for the Clan but it’ll be a memorable experience for those who take part. At the moment, my information is that I will be assisting the Salute Taker along with the Chief of Clan Gunn at the Edinburgh Tattoo on Saturday 5th August 2017 7:30 pm performance (NB there are two performances on a Saturday) that is a firm date. The Chiefs & their ‘retinue/clansmen’ will foregather at a designated point on the Royal Mile before the event & march into the arena. The Chiefs will then join the Salute Taker for the evening to take the salute whilst their clansmen watch from the edges of the arena & after the Ceremony of the Quaich all will proceed to their ticketed seats in the stands.

I’m delighted to say you will be able to join the group in the arena, the clans have been earmarked 150 tickets per clan per performance, the tickets are not discounted, cover a range of prices & parts of the arena & are subject to a booking fee, they went on sale on 21st November & sell like hotcakes, up to date 90,000 tickets have been sold already and note, any of our allocation not sold by 1st March 2017 will go on general release. Graeme and Gillian have already booked their accommodation and I understand Michael is hoping to make it too, therefore, the important thing is to put the date in your diary, get your tickets and come and join us at the Salute. In order to gauge support, we’re directing access through Graeme and the CFSSUK, security is essential, as we don’t want these popular tickets falling into the wrong hands and Graeme has the information you need to obtain the specially allocated tickets, there’s a separate webpage, a code and password, all quite simple and straightforward but essential for security, you will also be able to purchase up to eight tickets online. Graeme’s contact details are further on in the Newsletter but I’ll print them here as well, or go to the website and use the email address in the Links page editor@fraserclan.net

We look forward to the Tattoo event and seeing you there on Saturday 5th August. Kate Nicolson Fraser

HOUSE OF FREZEAU

The Link Between The Frasers And The House Of Frezeau De La Frezelière In Anjou.

By coincidence, our old friend André-Yves Bourgès posted on our website Guestbook a few weeks ago, reminding us about the link with Clan Fraser and the House of Frezeau de la Frezelière, it reminded me of the article I’d reproduced of Susan Boag’s in the 10th Anniversary Newsletter so it’s very fitting to reproduce it here. Susan makes a précis of the arguments in her article but the full version can be found via the link on André’s website posting on our Guestbook or type in http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/abpo_0399-0826_1996_num_103_4_3886

Inspired by the article Gil and I visited la Frezelière in and although there’s nothing left of the House of Frezeau, in Anjou, the village still exists and we took pictures to prove it but despite letters to the mayor I’ve been unable to find out anything more about any recent history. Ed

Inspired by the article Gil and I visited la Frezelière in and although there’s nothing left of the House of Frezeau, in Anjou, the village still exists and we took pictures to prove it but despite letters to the mayor I’ve been unable to find out anything more about any recent history. Ed

Susan Boag: This is not really my article at all. Most of it comes from a booklet produced by one of our members; André-Yves Bourgès, and translated from the French by a friend of mine, Amanda Tiddy. Alas, I do not have the space in this newsletter to give the full text of the original article, but I hope that I have given a true reflection of the argument. The author’s inspiration for this article comes from reading Sir Walter Scott’s novels. These novels are full of keys– interesting historical facts and puzzles that intrigue the reader.

The author of the article has been fascinated by the possible links between the Scottish Frasers and France – Scott’s books hint at this link, and although they are novels he feels that there is an historical basis for the link.

In the prologue to his novel Quentin Durward Scott recounts a meeting with a Marquis de Haut-Lieu. This Marquis was very pro-Scots because of links between his family and Scotland.

Quentin Durward was published in 1823. In 1832, another novel, Castle Dangerous, was published – it included a character called Marguerite de Haut-Lieu (daughter of a Norman noble settled in Scotland during the wars between Bruce and Balliol) who fell in love with Malcolm Fleming.

The author of the article suggests that there is no coincidence here – Scott uses the same family links in both novels. (NB Haut-Lieu is also written as Hattely by Scott showing the Anglicisation of the name). In Quentin Durward there is a reference to the links between the families occurring “at the beginning of the previous century” i.e. early 18th century.

The author knows of one other, relatively rare, case of mutual recognition of ancestral links. This relates to an act passed in Paris (9th April 1705) in which the House of Frezeau de la Frezelière (in Anjou) and the House of Fraser of Lovat (in Scotland) represented by the heads of these houses recognised the same ancestry.

The author of the article therefore suggests that we should read Frezeau or Frezel instead of Haut-Lieu or Hattely, and therefore Fraser.

Further evidence comes from the fact that the female heir of Sir Simon Fraser (executed in 1306 for involvement with Wallace and Robert the Bruce) married a Fleming. This matches the “imaginary” marriage between Marguerite Haut-Lieu and Malcolm Fleming in Castle Dangerous.

The author of this article is in no doubt that Scott wanted to indicate the two branches of the families (French and Scottish) which were descended from the ancient House of La Frezelière, i.e. the Frezeau and the Frasers.

Although this link between the Frasers and Frezeau is not actually proven, some eminent genealogists (Innes and Moncreiffe) acknowledge it). This author however, is concerned to identify how old the link between the families is.

The Wardlaw Manuscript refers to the French origin of the Frasers, but dates it very early and doesn’t refer at all to the family of Frezeau de La Frezelière. However, the book does tell us when the tradition of a link grew up.

When the book was written in 1666 there was no link made between the two families, yet we know it was acknowledged in 1705 through the act mentioned earlier. So, it is between these dates that the line of descent was accepted and it is in this period that two exceptional men lived – Le Marquis de La Frezelière and Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat.

When the book was written in 1666 there was no link made between the two families, yet we know it was acknowledged in 1705 through the act mentioned earlier. So, it is between these dates that the line of descent was accepted and it is in this period that two exceptional men lived – Le Marquis de La Frezelière and Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat.

The lineage of the Lords of de La Frezelière seems certain after the last quarter of the 13th century. At the beginning of the 18th century the heir to this noble line was Jean-Francois-Angélique Frezeau, Marquis de La Frezeliere (born 1672) who married Paule-Louise-Marie Briçonnet in 1690. This Marquis divided his time between Paris and a residence in Saumur and had a flamboyant personality.

In a similar way there was an equally colourful character found in Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat (born 1668). They were about the same age when he and the Marquis met. Simon Fraser was exiled to the Continent after problems in Scotland and he probably saw the opportunity to ingratiate himself with the exiled Stuart monarchs. Simon Fraser and the Marquis were both young men who had things in common. Although Lovat was in exile he was still valued as a contact by the Marquis de La Frezelière.

The author of this article then poses the question about which of these two men would have “worked out” the blood link between the two families.

Authors, like Sir Walter Scott, seem to be of the opinion that it was Simon Fraser when he returned to Scotland. He gathered around him a vast number of Fraser “cousins” as part of his retinue. Great dinners were held with up to 400 Frasers present. The extended family took in “Frasers” with very distant relationships with Lovat. However distant the relationship, these family ties were considered important. The author of the article suggests that even if not proven, the same desire to link the Frasers and the Frezeliere would have existed for Lovat while he was in France – he wanted to convince himself of the links.

The author acknowledges that these links were undoubtedly an illusion, but the need to “create” an extended clan or family was essential in the 17th and 18th centuries for the survival of a clan chief.

Right up until his death in 1711, the Marquis de La Frezelière had very fond feelings towards his “cousin” Lord Lovat, to whom he wished to marry his daughter. Even after his return to Scotland, the Marquis’ widow maintained a correspondence with her relative. There were clearly strong ties of friendship, whether or not there were strong ties of blood as well.

The ancient line of Frezeau de La Frezeliere died out in 1800 but the name continued to be found in Maine-et-Loire. The marriage of Isabeau Frezeau (dame du Chasnay) daughter of Lancelot (Lord de La Frezelière) to Jean de Quatrebarbes (Lords of Rongère) took the Frezelière bloodline outside Anjou. In fact, two daughters of this marriage married husbands from old noble Breton families during the 15th century so innumerable Frezeau descendants can be found in Brittany as well as Anjou.

The ancient line of Frezeau de La Frezeliere died out in 1800 but the name continued to be found in Maine-et-Loire. The marriage of Isabeau Frezeau (dame du Chasnay) daughter of Lancelot (Lord de La Frezelière) to Jean de Quatrebarbes (Lords of Rongère) took the Frezelière bloodline outside Anjou. In fact, two daughters of this marriage married husbands from old noble Breton families during the 15th century so innumerable Frezeau descendants can be found in Brittany as well as Anjou.

FAMOUS FRASERS/OR SEPTS OF THE CLAN.

JOHN SYME 1755-1831. THE BARD’S FRIEND

Son of the Laird of Barncailzie, Kirkcudbrightshire and like his father, a Writer to the Signet, young Syme spent some years in the Army, as an ensign in the 72nd regiment. He then retired to his father’s estate, where he experimented with farming improvements. His father lost heavily as a result of the Ayr Bank failure and Syme was no longer able to live at Barncailzie. Appointed to the Sinecure of Collector of Stamps for the District, Syme moved to Dumfries in 1791. His office was on the ground floor of a house, which is now Bank Street. When Robert Burns, a few months later, moved from his farm at Ellisland to the Wee or Stinking Vennel, he became a tenant of Capt. John Hamilton, on the floor above Syme’s office (Syme was his superior in the Customs and Excise).

Syme, a few years older than Burns, found Dumfries society dull and welcomed in the poet, a convivial kindred spirit. Burns was a frequent guest a Syme’s villa Ryedale, on the West side of the Nith. Of Syme as a host Burns wrote, in an impromptu verse:

“Who is proof to thy personal converse and wit,

Is proof to all other temptation.”

In the summer of 1794, Syme accompanied Burns on a tour through Galloway. The poet, smarting from the restrictions on his Jacobin sympathies, by the Commissioners of the Excise, apparently raged against the rich at the mere sight of a mansion. According to Syme’s remembered recollection of the trip, they rode to Kenmure the first day, then on to Gatehouse-of-Fleet, Kirkcudbright and St Mary’s Isle, where they were happily entertained by Lord Selkirk. Again according to Syme: “The poet was delighted with is company and acquitted himself to admiration…..” It was on this tour that Burns wrote “Scots Wha Hae” and a Thomas Fraser, bandsman, was involved with the tune.

Syme visited Burns at Brow on 15th July 1796, and again a few days later, when Burns had returned to Dumfries. He was horrified at the poet’s deteriorated condition.

After Burn’s death, Syme, with Dr Maxwell organised the funeral, and, with Alexander Cunningham, worked unsparingly raising money to help the poet’s widow and children and was the first to push for a Mausoleum to be built to hold the remains of the world’s greatest poet. He was one of those who urged Dr Currie to undertake his edition of Burns’s work, and along with Gilbert Burns spent three weeks staying with Currie at his Liverpool home.

Syme left some highly-coloured, though valuable, reminiscences of Burns. His correspondence with Cunningham came to light a few years ago.

Of Burns’s features, Syme wrote: “The poet’s expression varied perpetually, according to the idea that predominated in his mind: and it was beautiful to mark how well the play of his lips indicated the sentiment he was about to utter. His eyes and lips, the first remarkable for fire, and the second for flexibility, formed at all times an index to his mind, and as sunshine or shade predominated, you might have told a priori, whether the company was to be favoured with scintillation of wit, or sentiment of benevolence, or a burst fiery indignation…. I cordially concur with what Sir Walter Scott says of the poet’s eyes. In his animated moments, and particularly when his anger was aroused by instances of tergiversation, meanness, or tyranny, they were actually like coals of living fire.” (Editor)

ALEXANDER FRASER OF TOUCH FRASER AND COWIE

by Susan King

Susan King, the American granddaughter of a Highland Fraser, is a former university art history instructor and a multi-published novelist. One of her most recent books, Lady Macbeth: A Novel, is a February 2008 hardcover release from Crown/Random House, under the name Susan Fraser King.

Throughout Scotland’s fight for independence under Wallace and Bruce, the Frasers numbered among the patriots of the rebellion against English oppression. In particular, two Fraser names stand out among the rebels who fought for Scotland: Sir Simon Fraser, known as “The Patriot,” executed in 1306, and his younger distant cousin, Sir Alexander Fraser, a rebel knight who attained high office in Scotland and won the hand of the sister of the King of Scots. At the Battle of Methven in June 1306, Sir Simon Fraser is said to have saved King Robert’s life not once, but three times, when Robert repeatedly slid from his horse in the fray and the muck and Simon hefted him back into the saddle to fight on. But Scotland itself could not be saved at Methven: the surviving Scots, including the king and his men, were forced to flee. Simon Fraser and a few others were captured and hauled to London in chains. Some were hanged or beheaded, but Simon was singled out for the same punishment given his comrade William Wallace the previous year: crowned with periwinkles and put on trial, Simon Fraser was hanged, drawn and quartered. Alexander Fraser, a younger cousin a few times removed, also fought at Methven and fled with Bruce’s knights. He, too, was captured by the English, but somehow managed to escape and later rejoined Bruce and his men. Although not as much is known of Alexander as the more famous Simon the Patriot, what is recorded of Alexander Fraser indicates the same stalwart loyalty and bravery that characterized the finest of Scotland’s rebel knights.

Bruce, the Frasers numbered among the patriots of the rebellion against English oppression. In particular, two Fraser names stand out among the rebels who fought for Scotland: Sir Simon Fraser, known as “The Patriot,” executed in 1306, and his younger distant cousin, Sir Alexander Fraser, a rebel knight who attained high office in Scotland and won the hand of the sister of the King of Scots. At the Battle of Methven in June 1306, Sir Simon Fraser is said to have saved King Robert’s life not once, but three times, when Robert repeatedly slid from his horse in the fray and the muck and Simon hefted him back into the saddle to fight on. But Scotland itself could not be saved at Methven: the surviving Scots, including the king and his men, were forced to flee. Simon Fraser and a few others were captured and hauled to London in chains. Some were hanged or beheaded, but Simon was singled out for the same punishment given his comrade William Wallace the previous year: crowned with periwinkles and put on trial, Simon Fraser was hanged, drawn and quartered. Alexander Fraser, a younger cousin a few times removed, also fought at Methven and fled with Bruce’s knights. He, too, was captured by the English, but somehow managed to escape and later rejoined Bruce and his men. Although not as much is known of Alexander as the more famous Simon the Patriot, what is recorded of Alexander Fraser indicates the same stalwart loyalty and bravery that characterized the finest of Scotland’s rebel knights.

He was the eldest of the four sons of Sir Andrew Fraser, a knight listed as Sheriff of Stirling in 1293, and Beatrix, daughter of Sir Reginald le Cheyne of Duffus, Edward I’s lieutenant in Moray and Caithness. Andrew’s father, Richard Fraser, held the lands of Touch Fraser in Stirlingshire, and the line was descended from the Gilbert Fraser who had held Oliver Castle. When Alexander was a boy, his father was captured and taken to England, and forbidden to travel north; Beatrix and her sons—Alexander, Simon, Andrew and James—joined him in the south. At the time, Edward I required the sons of Scottish noblemen to spend time in his service and to swear fealty to him. At the king’s court, Alexander would have encountered other Scottish knights, likely including his distant kinsman Sir Simon Fraser, and Sir Robert Bruce, son of the Earl of Carrick, both of whom had sworn allegiance to Edward. A neat irony of the Scottish Wars of Independence is that the heart and soul of the Scottish rebellion was fostered in Edward I’s own court. A young knight though not yet a baron, Alexander left England for Scotland, and apparently followed Sir Simon Fraser and probably William Wallace as well. Soon he was with the force accompanying Robert Bruce after his secret crowning in March 1306 by the 19-yr-old Countess Isabel of Buchan, born a MacDuff and married to a Comyn. After Alexander’s capture and escape after Methven, he took to the hills with Robert Bruce, whom the English called “the king in the heather.”

Bruce led his men into the area of the Mearns, where Alexander and at least one of his brothers helped carry out the Scottish victory over the Comyns at the Battle of Barra Hill in the winter of 1308-09. This was also known as “the Harrying of Buchan,” when Bruce and his men destroyed the castles belonging to the earldom of Buchan, in accordance with Bruce’s policy of scorched earth and broken stone. By then, Lady Isabel of Buchan was an English captive, and though Bruce had much sympathy—and possibly affection—for that brave, tragic young woman, he had no love for her husband, John Comyn of Buchan, who lost his life when Bruce harried the region that winter. A MacDuff by birth, Isabel was one of the few who held crowning rights in Scotland. After Bruce’s kingmaking, she was captured in September, 1306 near Kildrummy with some of Bruce’s close kinfolk, including his brother Neil and brother-in-law Sir Christopher Seton; his queen, Elizabeth de Burgh; his daughter, Marjorie, age 12;, and his sisters, Lady Mary and Lady Christian, Seton’s wife. Neil and Christopher were executed when the party reached Berwick, and Edward I ordered quarters in English convents for Elizabeth, Marjorie, and the newly widowed Lady Christian. The English king devised a cruel punishment for Lady Mary and the Countess Isabel: two cages of iron and timber were constructed to his specifications and hung outside the walls of Berwick and Roxburgh castles, where the young women were confined and displayed in public for four years. Isabel was moved to a convent, then to an English castle where she either died or vanished to history; Mary was transferred to Newcastle for another four years of captivity, this time indoors. Robert’s continued efforts to ransom the Scottish women were unsuccessful.

Mary Bruce’s survival was of key significance for Alexander Fraser. When the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314—where Fraser and his brothers fought alongside Robert Bruce—shifted the balance in the Anglo-Scottish war, many Scottish prisoners were ransomed and released, but not all: a party of Scots, led by Sir James Douglas, attacked Newcastle and rescued Lady Mary Bruce. Once in Scotland, she was married to Sir Neil Campbell of Lochawe; it is possible they were wed before her capture. Neil, possibly much older than his wife, died late in 1315, leaving Mary a widow with a small son. Despite their status as barons and knights and more, until Bannockburn, Bruce’s men were essentially forest rebels, outlawed and hiding in the vast tracts of the Selkirk Forest and other areas. As Sheriff of Stirling and Baron of Touch Fraser, inherited from his grandfather, Alexander Fraser was in a position to aid the rebellion, as Simon the Patriot, also a sheriff, had done before him. Later, when Bruce had the means, he rewarded the loyalty of many of his men, including Alexander Fraser. Probably in his late twenties or early thirties by then, Alexander had proven himself—and soon earned not only property and titles, but the hand of the king’s sister. In 1316, he married Lady Mary Bruce. Their first son, John, was born in 1317, followed by William in 1318.

Bruce granted Alexander the rights to the counties of Forfar, Aberdeen, and Kincardine, along with properties that included Aboyne, Panbride, Cluny, Durris and Cowie (or Couy, as it was then). Holding vast lands and now a kinsman of the king, Sir Alexander Fraser was indisputably powerful, and by 1319, Bruce had appointed him to the post of Lord Chamberlain of Scotland.

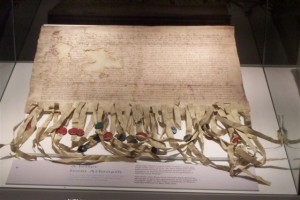

Sir Alexander Fraser’s seal and signature appear on the letter sent to the pope by the leaders of Scotland. The Declaration of Arbroath stated the Scottish leaders’ passionate belief in their right to freedom against English oppression. An original copy, now in Register House in Edinburgh, contains the signatures and almost half the seals affixed to the parchment, including that of Alexander Fraser: an armored knight holding sword and shield on a caparisoned horse, with a shield of six white strawberry flowers on blue. As Lord Chamberlain and brother-in-law to the king, and as one of the signers of that remarkable document, it is quite possible that Alexander Fraser helped compose its enduring statement:

For as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule. It is not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom–for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.

Alexander Fraser continued as Lord Chamberlain of Scotland until 1326. His wife, Lady Mary Bruce, died in September, 1323, after only nine years of her own reclaimed freedom. She left her husband with two small sons, John and William, and though it is unknown if he married again, it is certain he remained close to the throne. Following Bruce’s death in 1329, Alexander helped protect and advise young King David II—who was of an age with his Fraser cousins—and supported the continuing Scottish resistance against the English.

Alexander Fraser took part in the Battle of Dupplin Moor on 12 August 1332, a brutal battle that became a devastating defeat for the Scots. In its aftermath, the bodies of Scottish knights were piled higher than a tall upright spear. By all accounts, the English climbed the carnage to thrust spears and swords at anyone still moving. Among the Scotsmen lost that day were the earls of Mar, Moray, Menteith, and the late king’s illegitimate son, another Robert Bruce—along with Alexander Fraser of Touch Fraser, Durris, and Cowie. His three brothers, Simon, Andrew, and James Fraser, were lost a year later at the Battle of Halidon Hill in 1333, along with Mary Bruce’s eldest son, John Campbell. Alexander’s son by Mary Bruce, William, became the ancestor of the Frasers of Philorth (now Cairnbulg); Alexander’s brother James, lost at Halidon Hill, founded the Frendraught line. In addition, their brother Simon, also killed at Halidon, was the ancestor of the Frasers of Lovat. The heritage of the Fraser Sheriffs of Central Scotland included some of the finest heroes in an age of freedom fighters—and the sons of Andrew Fraser, including Alexander, contributed significantly to the strong foundation of Clan Fraser.

I’d like to thank Susan for giving her time, once again in writing for us. ©Susan Fraser King. Also, Historic Scotland for use of their images.

PAT FRASER Performer in the Doric

I became a Fraser in October 1970 when I was married. We moved to Edinburgh and lived there for 8 years, followed by 11 years in Aberdeen and have spent the last 18 years in Aberlour. We were blessed with a son and a daughter and now have 3 grandchildren It was not till we came to Aberlour that I even dreamt of ‘treading the boards’ so to speak and it was all because of a chance comment to a customer in the shop where I worked. I’d been to see a local drama production and said how much I enjoyed it – next thing I knew I was taking part.

I was also invited to join a choir, which I really enjoyed as well. Our choir had an annual concert raising monies for local charities and we were all invited to do a ‘party piece’. Being too terrified to sing on my own our choir lady said to do one of my speeches from a play – well that sounded daft to me – so I gave her Ian Middleton’s ‘Better a Grin nor a greet’ book of poems and asked her to choose one and I would do that.

The rest is history so to speak one poem is not enough so I learnt another and another and so on till I now have a repertoire of 30 +. It opened doors for me I didn’t know existed, and soon I was being invited to all sorts of ‘do’s’ and joined a concert party. The Prof from Moray Firth radio kept asking why don’t you make a recording – who me? My Mum was coming up to 80 – now what do you give your Mum that is unique for her 80 birthday – you’ve got it a CD called Hudin it Gyan. The reason for the title – Ian Middleton always signed his book ‘Hud the Doric Gyan’ (Keep the Doric going) With much secrecy and sneaking around I went to Acorn Audio in Findhorn and with the help and patience of Ian McIvor a CD was produced. The surprise it gave Mum was worth it – she has always supported me and been there for me. My husband, who is the true Fraser, gets involved in taking me to various venues and waits patiently in the wings. I am bringing out a second CD ‘Gyan at the Marie Curie Cancer Care Concert in Inverurie, part of the proceeds go to them as Mrs Middleton requested.

A wee taster

The tatties ma faither gew were nae great dale An nae muckle ees for the show The mannie neest door, a great gairdenin rival At the chance o a dig wisna slow A gie peer crappie for sic a gweed eer Ye’d maybe be better wi floo’ers. Thers’ nithin adee wi ma tatties said faither They were groun ti fit my moo nae yours!

Doric, according to Wiki, is the popular name for Mid Northern Scots or North East Scots, refers to the dialects of Scots spoken in the North East of Scotland.

The Battle of Blar na Léine

Seen on a dreary, cold October day, the swampy reed bed at the head of Loch Lochy, along the A82 toward Fort William, seemed unremarkable. Although no sign marked the place, the local directions had been good, and I was sure of the location. I stood gazing at the site of Blar na Leine, one the most devastating encounters in Highland clan history.

A car park below the Laggan Lock edges the northeast head of Loch Lochy. Tucked between the sandbank and the road, a watery thicket of golden reeds blurs the head of the loch. This is part of the field  where the Frasers once met the MacDonalds in the battle called Blar na Léine, or Field of Shirts. When Alasdair, sixth chief of Clan Ranald died–some say killed by his own kinsmen–a dispute arose over who should succeed him. The fourth Clanranald, Alan MacRuari of Moidart, beheaded in 1509 by order of James IV, had left a son, Ranald, by his wife Isabella Fraser, sister of Hugh Fraser, then Lord Lovat. Known as Ranald Gallda–the stranger–the son of Alan MacRuari was fostered, by Highland custom, by his mother’s people. In his absence, the MacDonalds turned to Ranald Gallda’s cousin, an illegitimate son of the sixth Clanranald by a handfast union.

where the Frasers once met the MacDonalds in the battle called Blar na Léine, or Field of Shirts. When Alasdair, sixth chief of Clan Ranald died–some say killed by his own kinsmen–a dispute arose over who should succeed him. The fourth Clanranald, Alan MacRuari of Moidart, beheaded in 1509 by order of James IV, had left a son, Ranald, by his wife Isabella Fraser, sister of Hugh Fraser, then Lord Lovat. Known as Ranald Gallda–the stranger–the son of Alan MacRuari was fostered, by Highland custom, by his mother’s people. In his absence, the MacDonalds turned to Ranald Gallda’s cousin, an illegitimate son of the sixth Clanranald by a handfast union.

John of Moidart–Iain Moidartach–was legitimized in 1531 by an Act of the Privy Council and assumed the chiefship. In 1540, he rebelled with several other Highland chiefs after James V annulled their charters, and was arrested and imprisoned in Edinburgh. Meanwhile, Lovat came west with his men to install Ranald in Castle Tioram. Ranald must have been a little over thirty years old, judging by the date of his father’s death. According to tradition, upon seeing sheep and oxen roasting for a great feast in his honour, Ranald Gallda remarked that the fuss was unnecessary–roast chickens would have done well enough. However he meant it, the remark insulted the MacDonalds, who dubbed him “hen chief” and sent him packing. He returned to the Fraser stronghold at Beaufort Castle, and shortly afterward, MacDonalds boldly laid waste to Fraser lands in Glenelg. Escaping prison in 1542, John of Moidart marshalled his men to further oppose Ranald, who not only had a solid claim by birthright, but the Frasers at his back. Moidart and his allies raided parts of Urquhart and Glenmorriston, belonging to Grants allied with Frasers. They then ruined Fraser properties at Strathglass and Abertarf. Aware of the turmoil in the north, the Earl of Arran–regent to the infant Mary Stewart– appointed the Earl of Huntly as his lieutenant-general in the Highlands, hoping to circumvent trouble.

As tensions escalated, Huntly gathered an army and marched north in May, 1544, accompanied by Frasers, Grants, and Macintoshes, to meet a faction of Clan Ranald and their allies, Clan Cameron. In mid-summer, 1544, John of Moidart and his men met and mediated with Huntly and his forces, and agreed to depart for the west. In July, 1544, Lovat and the Frasers headed home through Glen Gloy, accompanied by Macintoshes and Grants. Fraser parted company with Huntly and the others, who headed across the Spean valley. Lovat took the direct and shortest route to Beauly through the Great Glen, by way of Loch Lochy and Loch Oich. He dispatched some men under Iain Cleirich, who may have been a cleric, to scout for danger, knowing the MacDonalds had recently headed west. Although Iain and his men did not return, Lovat continued to head northeast for home. John of Moidart, with a company of five hundred MacDonalds and Camerons, had rounded on his westward course to camp his men on the lower slopes of Ben Tigh, a secure vantage point over the northern side of the glen. On the 15th of July, a hot and sunny morning, they rested, and ate oatmeal mixed with water from a small lochan nearby. Perhaps the more hungry among them drew blood from nearby cattle to make their cold oats more hearty. Then each man drove a notched stick into the soft, peaty soil, a common practice among Highland warriors; afterward, the unclaimed sticks would leave a grim accounting of the dead. The MacDonalds then waited.

Lovat’s company of Highlanders, which included at least three hundred Frasers and a respectable number of Grants, approached the north end of Loch Lochy in order to cross the swampy meadow there and turn northeast for Beauly. With them was Lovat’s nephew, Ranald Gallda. Lovat had earlier instructed his own son, Hugh, the Master of Lovat, newly returned from his studies in Paris, to stay home. As Lovat and his men rounded the end of the loch, Moidart’s men swept across the burn that cuts the brae at the foot of Ben Tigh.

The day was brilliantly sunny, with the sort of sweltering heat that comes only once in a while to the Highlands. Clashing on the reedy, swampy shores at the head of Loch Lochy–the loch was lower then, and the field larger–the two groups met. Trapped in ambush, the Frasers and Grants defended as best they could. The skirmish erupted with bows and arrows at a distance, but soon the shafts were gone. Drawing closer, apparently determined to see an end to the conflict, both sides drew out heavier weaponry, including sturdy Lochaber axes, and the huge two-handed claidheamh mór that measured from a man’s chin to his toe. Unforgiving, unrelenting hack-and-slash combat is art and part of such weapons, and the men struggled fiercely and violently on the reedy banks of the loch, in hot, unrelieved sun and heat. An old account mentions the use of firearms at Blar na Léine. This would have meant clumsy, expensive match-lock pistols that were cumbersome to load, but once fired, served well for bludgeoning. With some sword blades and axes broken, and fired pistols cast aside, the men resorted to long dirks. Each side refused utterly to give up. Under the blazing sun, the watery field absorbed a massacre.

Perhaps the baking heat and intense sunlight increased the maddening scent of blood and sweat, magnifying anger and diminishing reason. Whatever happened, the battle raged on. The men are said to have torn off their garments, fighting half-clad or even naked. Later the field was littered with hundreds of mutilated bodies. Scattered among them were the pale, blood-stained linen and flax shirts that they had worn beneath their wrapped and belted plaids. For this reason, the battle is still remembered as Blar na Léine, or Field of Shirts (Blar can mean battlefield as well as level plain).

Likely those men who wore armor, including hot, lined helmets, hammered steel breastplates with quilted gambesons beneath, and heavy jacks of iron-studded, quilted canvas, cast those aside to seek relief from the sweltering heat. Shirts were discarded by the hundreds, and some threw off their woolen plaids as well. The struggling Highlanders must have looked more like wild, furious ancient Celtic warriors than men of the sixteenth century. In part, it is this heedless, courageous stripping away of encumberments to release raw power and fury that marks this battle as memorable and astonishing.

Those who died among the Frasers included Hugh Fraser of Lovat–Mac Shimi himself–and Ranald Gallda, whose stranger status had sparked the tragedy. The young Master of Lovat, who had arrived halfway through the fray against his father’s orders, was wounded and captured, and died days later. Ranald Gallda’s own sword, it is said, was once owned by a MacDonald family in Strontian, who proudly displayed the nicks in the steel. Among the host of Frasers and Grants, tradition claims that less than half a dozen men–accounts report one to five–walked away from that bloody field. Clan Ranald and the Camerons, with their larger numbers, fared proportionately worse at the hands of the Frasers. Only eight or ten men reclaimed their notched sticks from the brae at the foot of Ben Tigh. One of them was John of Moidart himself, who, though severely wounded, recovered. Although the Earl of Huntly pursued him to exact revenge for the devastating July battle, John of Moidart survived that as well, and continued to lead his clan for another thirty years. The warrior forces of Clan Fraser were nearly annihilated at Blar na Leine, but a legend arose from the tragedy. Clan tradition holds that eighty Fraser women who were widowed that hot July day were left pregnant. Within months, eighty healthy sons were born to them, bringing new life and new hope into the depleted clan.

Eighteen years after Blar na Léine, the new Fraser chief, Lovat’s seventeen-year-old nephew, another Hugh, mustered his men–many of them his own age, if the legend is true–to greet Queen Mary Stewart on her progression to Inverness. Young Lovat, said to be good-looking and only a little younger than the queen herself, earned Mary Stewart’s favour, and in fact offered to lend his Frasers to the queen’s service.

Years later, this new Lovat and John of Moidart inexplicably became allies. If so, that would reinforce Moidart’s reputation among Clan Ranald as one of its strongest and finest leaders, and also implies that the next Hugh Fraser of Lovat understood the advantage of tolerance over vengeance. It is interesting to speculate that, in the aftermath of the massacre, the influence of the mothers and females left behind in the two great clans might have encouraged diplomacy between the enemies. By one means or another over the years, Clan Fraser was restored to strong numbers. When Hugh Fraser of Lovat died in his early thirties, his clan, once decimated on a hot, sunny afternoon, mustered nine hundred warriors to attend his funeral.

The yew tree, long revered by Clan Fraser as their plant badge, became a prophetic symbol for the clan on a summer day in 1544. Like the tree that renews itself from within its own branches, Clan Fraser restored itself after the tragedy at Blar na Léine, and grew stronger and larger than ever before.

Directions to the site: Passing Loch Oich along the A82 from Inverness to Fort William, watch for the sign for Loch Lochy, past Laggan. The field edges the northern tip of the loch to the right of the road.

SOURCES: Fraser, Antonia, Mary Queen of Scots, London, 1969. Fraser, C.I. of Reelig, The Clan Fraser of Lovat: Johnston’s Clan Histories, London, 1952. Grant, Neil, Scottish Clans and Tartans, London, 1987. Morton, H.V. In Scotland Again, London, 1933. www.electricscotland.com/history, Clanranald and Lord Lovat– Field of Shirts.

Field of Shirts.

SUSAN FRASER KING, the great-granddaughter of Highland Frasers, is the author of twelve historical novels published by Penguin/NAL Signet. A PhD candidate in medieval art history, Susan lives in Maryland with her husband, their three sons, and a Westie puppy.

This work may not be reproduced without permission, © Susan Fraser King

A classic tale and one of the few stories about Scots in the 100 Years War.

DAVID SIMSON THE LEPER GUARDSMAN A SAD TALE FROM 15TH CENTURY FRANCE

A common feature of medieval and early modern monarchies in Europe and beyond was that they entrusted the personal safety of the monarch to foreign guardsmen, deemed more reliable and less involved in local politics than native soldiers. The Byzantine emperors had their Varangian guards, drawn from the Viking lands; the kings of Hungary were protected by Cuman steppe nomads. The 15th century kings of France looked to Scotland for their bodyguards. The precise date at which the so-called “Garde Ecossaise” was founded remains shadowy; it appears to have been in existence by 1425 and may possibly date back to the late 1410’s. The organisation remained nominally in existence until the French Revolution and was only finally disbanded in 1830, though it had long since lost its Scottish character by that date. During the 15th century, however, it was very definitely staffed by Scots. Its members were in very close attendance on the person of the monarch, and were well paid for their services. Their role was not always a comfortable one.

For one thing, the Garde remained a fighting unit and several of its members were to be killed in action protecting King Louis XI at the Battle of Montlhery in 1465. For another, the central role of the Garde in protecting the king from internal as well as external foes ensured that the monarch took a very close personal interest in the loyalty of its members. In theory the foreign nature of the guardsmen was supposed to insulate them from local politics; in practice, as they became long-term residents in France, they became increasingly absorbed into the life of that country and came to take on local loyalties. At times of tension this could lead to large-scale purges of the Garde to get rid of men whose loyalties were deemed doubtful. The 1450’s were an unstable decade in French politics, despite final victory over the English in the Hundred Years War.

The king, Charles VII (perhaps best known to English-speaking audiences as Joan of Arc’s “Dauphin”) was growing old and his relations with his eldest son, Louis, were very bad- in 1456 Louis ran away to the court of the Duke of Burgundy. The decade was full of show trials in which those suspected of undue sympathy to Louis faced trumped up treason charges. The Garde was not immune; its second-in-command was executed in 1455 and its commander exiled. At some point in 1459 one David Simson joined the Garde as one of a group of 48 archers under the command of Patrick Folcart (to use the French spelling of his name). Folcart also commanded 31 men-at-arms (more heavily armed and better paid troops); there was also an elite group of 24 additional Scottish archers under a French commander. We know nothing much about him beyond his name. Possibly he had been recruited from the Scottish unit which served in the ranks of the French royal army- joining the better paid elite Garde would constitute a distinct promotion. Simson may well have served the King of France for many years since we know from disciplinary cases that other members of the Garde had been fighting in France in the 1430’s. He may have sailed to France with one of the large Scottish armies which had gone there in the early 1420’s. In other words, he may have been very much a veteran soldier with years of life and warfare in France behind him- we know of Garde members who retired due to age and infirmity. Simson served in the ranks of the Garde for some four years.

He survived the massive purge and reorganisation of the Garde which took place when Louis inherited the throne in 1460. Folcart was sacked along with about a quarter of Garde. New captains and a large number of new archers came in; the men-at-arms vanish. The new structure was about a hundred strong; an elite group of 25 and a further 74 men, all archers. Simson was in the latter group. Obviously his political loyalties, wherever they may have been, were acceptable to the new regime and he was not obliged to follow Folcart into the service of Louis’ younger brother Charles. He would have remained in close attendance on the king, mostly in the palaces of the Loire valley which had become the favoured area of royal residence by the 1450’s. No doubt he would have been very visibly on duty at royal entries to cities or protecting the king at court ceremonies (paintings of the period show the Garde in its distinctive red, white and green surcoats in attendance on French monarchs- even guarding Charles VII depicted as one of the Magi at the Nativity in a miniature in the Hours of Etienne Chevalier, now in Chantilly). Perhaps he hoped for promotion to the elite group of 25.

Alas, the accounts for 1463 show David Simson being pensioned off because he had “become leprous”. We cannot be sure what this really means. Late medieval doctors were inclined to diagnose a whole range of skin complaints as “leprosy” and medical historians would argue that “true” leprosy was very rare in Europe by the 15th century. If the disease Simson suffered from was leprosy, then it would have been a disaster for an archer given its propensity to attack extremities such as the fingers. Even if it was not (and we know nothing more of his fate), the social consequences of the diagnosis would have been serious even if it is clear that medieval lepers were nothing like as strictly segregated from the wider community as legend would have it. The only consolation, perhaps, is that he was paid off with a decent sum of money. It is hard to say how much exactly as the entry in the accounts refers to two other individuals leaving the Garde at the same time, but since one of these had just murdered the other one may assume that most of the 216 “livres” allocated would go to Simson- interestingly it looks as if 216 livres was more or less a year’s pay for an archer. This was quite a respectable sum and would at least have enabled him to purchase a place in a decent class of leper home, where one might imagine this old soldier bossing the other inmates round in Scottish-accented French!

The author’s full title is Dr Brian GH Ditcham (MA St Andrews, PhD Edinburgh) 22 Belmont Road, Gillingham, Kent, ME7 5JB,. He’s a native of Stirling, the son and grandson of Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, a French medieval specialist and earns his crust working for the DTI. He has published on Scottish mercenaries in 15th century France, although, his PhD thesis remains unpublished. He’s not a CFS member just someone I met on the net, with some fascinating stories to tell and I must thank him for his time and effort. (There is a famous picture Joan of Arc with her Garde Ecossaise but there’s no evidence that they guarded her) Editor

All content on this website is the copyright of CFSSUK ©